Show EU staff NHS needs them call

The number of EU nurses registering in England has fallen by 92 per cent since the Brexit referendum while the number of European NHS nurses who have quit their jobs has increased, new figures show.

The shocking statistics have been blamed on the government’s refusal to guarantee the rights of EU citizens living in the UK.

Just 96 EU nurses began working in the NHS in December 2016. In July 2016, one month after the referendum, 1,400 EU nurses joined the NHS.

A freedom of information request to 80 of the 136 NHS acute trusts in England by the Liberal Democrats also showed that 2,700 EU nurses left the NHS in 2016, compared to 1,600 in 2014 – an increase of 68 per cent.

Government failed

Unite national officer for health, Colenzo Jarrett-Thorpe, said the government has failed to train enough nurses and could not afford to leave EU staff in a position of uncertainty.

“The health service is already chronically understaffed. Not only is the government’s refusal to guarantee the rights of EU citizens residing in the UK morally wrong, it is causing valuable EU nurses working in the NHS to reconsider their positions at a time when they are desperately needed,” he said. “Through its belligerent hard Brexit stance and its use of EU citizens as political tools this government has also severely restricted the number European nurses coming in work in Britain.

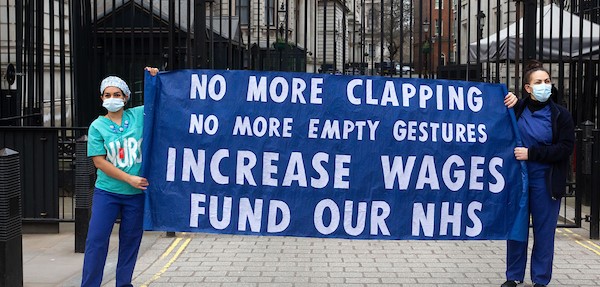

“As a matter of urgency Theresa May must show EU nurses and other EU healthcare professionals that they are wanted and needed in the NHS.”

Around 57,000 EU nationals work in the NHS, including an estimated 10,000 doctors and 20,000 nurses.

Morale

Morale is at an all-time low among EU healthcare staff, explained NHS occupational therapist, Anke Plummer.

Plummer, who is campaigning with Unite to guarantee EU citizens residing in Britain full rights, has lived in the UK for 27 years and used to describe herself as a “Brit with a German passport”.

“I never thought about being foreign and now I do. I’ve had eight months of being constantly told by the government, politicians and the media that I’m an immigrant and I’m somehow a part of the problem. I don’t feel British anymore,” Plummer said.

“I went to Germany a couple of weeks ago and for the first time in 27 years I made some enquiries about working there. I know other people I speak to who are thinking of going back home.”

She added, “There also used to be a constant stream of EU citizens applying for jobs and coming to the NHS, which has dropped dramatically. That’s going to be a problem in itself – never mind people packing their bags and leaving.”

Heaping on pressure

The fall in European nurses is heaping pressure onto the crisis hit NHS, which is already struggling to recruit staff. Since the bursary for trainee nurses was scrapped in early 2016, applications for nursing courses dropped by 9,990 to 33,810 in 12 months, figures released by UCAS in February show. A third of nurses are due to retire in the next decade, while 24,000 nursing roles remain open, according to the Royal College of Nursing.

While a department of health spokesperson insisted that the “secretary of state has repeatedly said that overseas workers form a crucial part of our NHS and that we value their contribution immensely,” Plummer said the government’s decision to use EU citizens as a negotiating tool in the upcoming Brexit negotiations signalled the exact opposite.

She said, “You cannot say that you respect and value people and then at the same time say they are bargaining chips and they will be treated as a resource. Actions speak louder than words.”

Like

Like Follow

Follow