Surveillance nation

The UK is one of the most surveilled nations in the world – nearly 6m CCTV cameras watch us as we go about our daily lives.

And now, this surveillance culture may be seeping into the workplace, a TUC report published this last week (August 17) discovers, with more than half of UK workers reporting that they believe they are being monitored by their superiors in work.

This surveillance can take many forms – the most common type reported by staff in the TUC survey is the monitoring of workplace emails, files and browsing histories as well as CCTV and phone logs and calls, including the recording of calls.

But with technological advances comes even more sinister modes of being watched by your boss, such as facial recognition software and handheld or wearable tracking devices. Such monitoring made headlines when it was revealed Amazon has patented wristbands to track warehouse workers.

But hi-tech workplace spying may be more common than previously thought. The TUC survey found that a quarter of people believed that tracking devices were used by their employers to monitor them, while 15 per cent believed they were being watched through facial recognition software.

The vast majority – 70 per cent – of workers polled said they believed workplace surveillance would become more common in the future, while a majority also objected to the most invasive forms of being watched, such as webcams on work computers and monitoring employees’ social media outside of work hours.

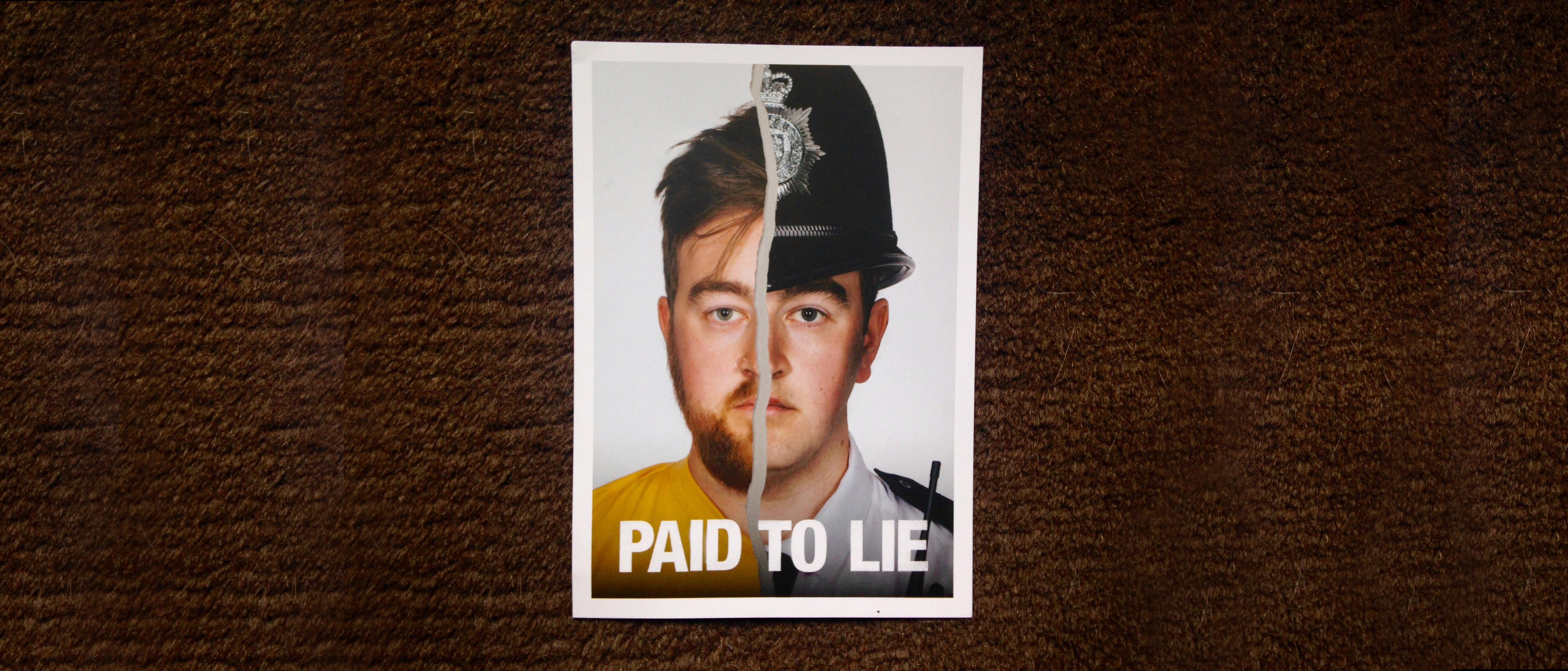

BBC Radio 5 Live spoke to workers of their experience of workplace surveillance.

One worker said he was told to ask staff to install software that he initially thought was to be used for time management.

“[It] turned out it was tracking all browser activity and could even take a photo of them every 10 minutes to check they were still at their desks,” he said. “I was a bit shocked and uninstalled.”

Another worker, a driver, told the BBC that monitoring while driving has left him “stressed out.”

“When I’m driving I’m more worried about what my driving score is than actually concentrating on driving the lorry,” he said.

Unite, which contributed to the TUC research, highlighted the increased use of surveillance among employers. The union found that a number of companies use dash cams and vehicle monitoring technology, while others are pushing for body cameras to be worn but so far unions have successfully pushed back.

Workers in the sector have objected to the surveillance, especially when it’s used as evidence in disciplinary hearings to review less-than-perfect driving.

EDF victory

Unite regional officer Onay Kasab gave the example of EDF workers who took strike action objecting to installing vehicle trackers in their cars.

“EDF first installed trackers in 2006 and staff morale totally tanked when management used the tracking devices in a bullying way,” he told UNITElive. “They reintroduced the trackers this year and there was the risk that they would be using the trackers as evidence in disciplinary hearings. Thanks to EDF workers’ brave stand in taking strike action, management dropped the plans. Now, the trackers have been removed and any surveillance footage will be inadmissible in disciplinary hearings.

“The entire system is now designed with safety in mind and not surveillance for surveillance’s sake,” Kasab explained.

“This is a great example of how trade unions can really make a difference in workplaces that are being subject to management spying,” he said.

Kasab gave another example of UPS parcel delivery workers being tracked by their bosses if they take â€inefficient’ routes.

“They are deliberately overloaded with an impossible workload,” he said. “Then they use the tracking information to discipline them for not taking the most efficient routes.”

Consult with staff and trade unions call

Workers as a whole, the TUC noted, are clear that there must be a line drawn over what’s should be considered acceptable and unacceptable monitoring. Overall, they agree that employers should consult with staff before introducing new forms of surveillance, and bosses should fully justify their use before they are introduced.

Workers moreover want regulations introduced so that surveillance isn’t used in a discriminatory way.

Kasab agreed that there should be limits on workplace surveillance, and when it is used it should be employed to protect workers’ safety.

“It can be used as a tool for good – for example, in the case of traffic wardens in Hackney, London, where camera footage has been used to monitor abuse against staff; we’ve had members who’ve been threatened with knives,” he said.

“At the same time, there needs to be better use of this safety surveillance – management may use it to identify a problem, but they rarely take action on it; they rarely think, â€what should do in the future to prevent abuse?’”

TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady said that surveillance should not be wielded as a weapon meant to keep tabs on workers.

“Employers must not use tech to control and micromanage their staff,” she said. “Monitoring toilet breaks, tracking every movement and snooping on staff outside of working hours creates fear and distrust. And it undermines morale.

“New technologies should not be used to whittle away our right to privacy, even when we’re at work. Employers should discuss and agree workplace monitoring policies with their workforces – not impose them upon them.

“Unions can negotiate agreements that safeguard workers’ privacy while still making sure the job gets done. But the law needs to change too, so that workers are better protected against excessive and intrusive surveillance.”

Kasab agreed.

“In the case of EDF, members had to take eight days of strike action – that’s eight days of lost pay – to put a stop to surveillance methods that they strongly felt crossed a line,” he said. “They would not have had to had there been legislation in place that requires bosses to consult with their workforce and trade unions before snooping on staff.”

Like

Like Follow

Follow