An impossible job

After being pummelled by years of a twin crisis in funding and recruitment, access to NHS care is now dangerously out of reach for patients up and down the country.

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine has warned that patients’ lives are at risk if urgent action isn’t taken to address the shortage of emergency doctors.

The warning came as a United Lincolnshire hospitals NHS trust (ULHT) is considering taking the unprecedented decision to temporarily shut an A&E it runs at night because there are simply not enough doctors on hand.

“We haven’t made a final decision yet, and we hope to avoid this, but the reality is we will need to temporarily reduce the opening hours of A&E at Grantham,” ULHT medical director Dr Suneil Kapadia told the Guardian. “The quality and safety of patient care is the trust’s number one priority and we haven’t rested on our laurels.

“We have tried to recruit in the UK and internationally, and we have offered premium rates to attract agency doctors whilst investing £4m in urgent care services. Despite this, we have reached crisis point.”

In response to the potential decision to reduce opening hours at Grantham A&E, Royal College of Emergency Medicine president Dr Clifford Mann said that in under-resourced locations, the “great efforts made by doctors and nurses to help patients” is often “not sustainable”.

“As well as potentially putting patient safety at risk, placing an ever increasing workload on overstretched staff can create a vicious circle in retention and recruitment with many overworked trainees simply choosing to leave the country or indeed the specialty altogether,” he said.

“The wider picture is there is a real crisis in emergency medicine as our workforce numbers are not growing fast enough to keep pace with rising numbers of patients attending A&E Departments.”

‘It all stacks up’

Unite national officer for health Sarah Carpenter noted that there’s a staffing problem right across the entire NHS.

“There’s a serious supply problem with GPs, for example,” she said. “And since there’s not enough GPs, people have no other option but to turn up at A&E. And then the A&Es can’t cope. It’s not the fault of individual trusts and how they manage; it’s the demand in a particular area.

“And then the minute you try to get other professionals to fill the gaps – there are things that can be done with specialist nurses or with physios or other medical professions – you find that they too are also in shortage. So you just keep moving the problem.”

“On one the other end, there are porters who are being expected to cover nursing duties because there’s a shortage of nurses,” she explained. “So everything shifts up and stacks up and it affects all grades in the NHS.”

Indeed, in a recent Care Quality Commission report which looked into the failings at North Middlesex hospital, the NHS care regulator found that its A&E was so understaffed and busy that untrained receptionists were being asked to judge which patients needed to be seen first.

‘How would you manage?’

Carpenter highlighted that “very difficult decisions have to be made locally” and the ultimate culprit is inadequate funding.

This was nowhere made more apparent than in Merseyside, where the St Helens clinical commissioning group has for the first time proposed, among other ideas, to suspend all non-urgent treatment for four months in an attempt to tackle its shortfall in funding.

Dr Richard Vautrey, deputy chairman of the British Medical Association’s GP committee argued that halting non-urgent treatment across-the-board was a very dangerous move and one that showed just how desperately the health service needs greater funding.

“What apparently may not be urgent at first presentation and is therefore not referred could turn out to be very serious in the long term,” he said. “Many cases of cancer are subsequently diagnosed following routine referrals of patients who have undifferentiated symptoms early on in their illness.”

St Helens CCG chair Geoffrey Appleton explained their decision to put a series of proposals up for public consultation to determine which services will be suspended, withdrawn or reduced.

“To explain it in simple terms, imagine our NHS budget is your household budget and every year the cost of living goes up but your salary doesn’t increase,” he said. “The result is money becomes tighter and tighter. Now imagine another relative comes to live with you and because of their health needs are unable to work and cannot contribute financially. How would you manage?”

Vice president of the Royal College of Surgeons Stephen Cannon believes that what’s happening at St Helens is “not just a one-off; this is a growing problem across the NHS” and Carpenter agrees.

“I think this problem is definitely spreading,” she said.

The blame, Carpenter argues, should fall squarely on the shoulders of both funding arrangements as well as the structural problems that are plaguing the NHS.

“The constant change in structure is a huge problem,” she explained. “CCGs themselves potentially become part of the problem because they exist to commission out services which don’t do anything but cost a lot of money.”

Change course now call

Carpenter fears that the government’s chronic underfunding of the NHS is a deliberate move.

“You could view all of this as a bigger attempt on the part of the government to say, well the health service looks like it’s on its knees, therefore we should privatise it,” she explained. “Their policy will be, â€How far can we go to destroy the NHS so that privatisation can go through smoothly?’ – they think, ‘well, no one will object to a rundown service being taken over’.”

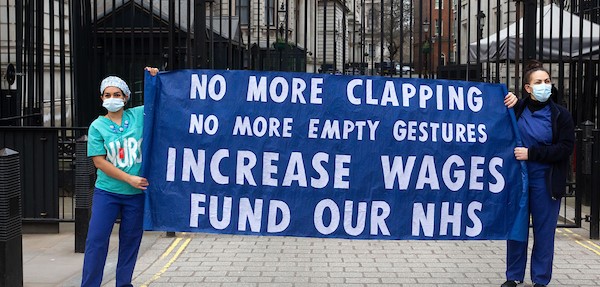

Carpenter said that Unite is calling on the government to change course immediately to save an NHS that desperately needs support.

“Our message is this — invest properly in a national health service. Stop believing that it can be done better by private companies.”

She argued, too, that the NHS staff who work incredibly hard to keep the service running should be treated with respect, instead of with the derision that was most recently exemplified during the junior doctors’ dispute.

“Trust the people who are currently running the service to deliver that service and give them the proper tools to do that,” Carpenter urged the government. “Stop blaming them every time that there’s a problem. Acknowledge that those who are running the service are trying their best to do an impossible job.”

Like

Like Follow

Follow