Portrait of disparity and despair

With her clouded eyes brimming with tears, Mary wails inconsolably. She reaches out her arms toward me, begging, “Please, please, take me home.” I anxiously glance around the living room where Mary has been confined for years since age weakened her body and dementia stole her mind.

“You are at home Mary, this is your home.”

I try to reassure her, speaking slowly and clearly. Mary sobs louder still, looking at me with desperation. I have no idea what to do. She has been crying now for almost four hours.

Unqualified and inexperienced, I’ve been employed as a carer for Mary. I hear the front door slam as her family leave to find some peace and quiet. It seems absurd to me no one would mind that I’ve never cared for an elderly person in my life, or that no one would want to see an NVQ certificate, CV or reference before leaving a dementia patient in my care.

Fortunately for Mary and her family, I am a trustworthy person and feel a great deal of compassion for her. But as she cries and cries and nothing I do or say seems to soothe her, I am acutely aware of how hard this job is and how important adequate care is to dementia patients whose suffering can be so intense. I won’t do anything to harm Mary, but my lack of training is surely a risk to her health and wellbeing.

Mary’s family pay me from a personal budget they receive from the council, as an alternative to placing her in a nursing home.

“She wouldn’t want to be away from family; her home is where she belongs,” Mary’s daughter once told me. I can understand this, and this option should take some strain off of NHS hospitals.

But, under the Con-Dem’s 2014 Care Act, this funding is available without any prior safeguarding checks into the quality of care it pays for. I got this job through a friend of a friend, and now I wash, lift, feed and administer medication to a very elderly dementia patient. No training required, no experience necessary and no criminal checks have been conducted.

Fiona Farmer, national officer for local authorities at Unite, says this system flaw is a result of cuts from central government and goes some way to explaining the alarming disparities in the provision and standard of dementia care across England, exposed in Jeremy Hunt’s Dementia Atlas.

“In the last six years £20bn has been cut from local council budgets,” Farmer says. “And these disparities in dementia care can be directly linked to the highest level of cuts in local councils with the most deprived authorities.”

Local authorities simply can’t afford to make sure that the personal care budgets given to dementia patients are being used in a safe and responsible way, which is why situations like Mary’s, where outsourcing care services and arranging carers through not-for-profit organisations, are increasingly common.

For the Tories, this is a simple way of shirking responsibility while dressing it up as giving autonomy to the â€service user’. But for the human being suffering with dementia, like Mary, it is laden with risk and gambles with the lives of some of the most vulnerable people in our society.

Mapping dementia care

Hunt’s interactive Dementia Atlas shows dementia care to be a postcode lottery, with some parts of the country receiving care more than three times as bad as others – and the divide is political.

“The most deprived authorities are mostly Labour councils, suffering cuts of 20 to 30 per cent, whereas the least deprived Tory councils are being cut nearer to 5 per cent,” Fiona explains.

The Dementia Atlas confirms that this political destabilisation is directly affecting dementia care: in Labour stronghold Merseyside – where some council budgets have been cut by £16m this year – 80 per cent of dementia patients are taken into hospital, but in Tory controlled Kent this figure drops to 16 per cent.

Hunt said that he hoped the atlas would “shine a spotlight” on the worst performing areas, but the map would provide a much more accurate account of the healthcare situation if local authority funding cuts were also included.

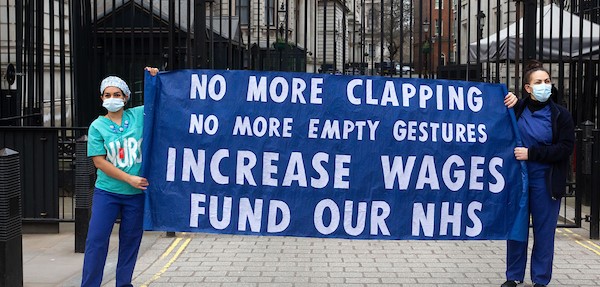

“The funding disparities from central government is setting the system up to fail,” says Unite national officer for health Sarah Carpenter.

“The lack of proper funding means that families are having to find alternative solutions for care,” Sarah says. “If Jeremy Hunt was really committed to improvements in healthcare, he would be funding a better system.”

Funding for all

Eventually my shift ends as the next carer arrives – a mother of three young children who needs the money. Mary is still crying as I close the door behind me. The next day she has a panic attack as another under-qualified carer is moving her into the bathroom. Emergency services are called and she is taken to hospital where her condition worsens.

A chronic and degenerative brain disease like dementia makes people like Mary incredibly vulnerable, so it is vital that our health and social care system is funded to safeguard all those who suffer from it.

Until responsibility is taken to protect and care for vulnerable adults, to make sure they can live at home with dignity and are treated with compassion by trained professionals, Hunt’s Dementia Atlas will remain a portrait of disparity and despair and more people like Mary will be lost to it.

Like

Like Follow

Follow